Are there new forms of migration? (collective rationales)

Several factors may be the cause of (new) migrations: socio-economic and of course political contexts in the departure countries and the arrival countries, demographic and economic divisions between countries and continents, gaps between levels of human development (life expectancy, education level, standard of living), globalisation (which, while increasing exchanges and encounters, is disrupting spaces and imaginaries), geopolitical and regional (re)configurations, new conflict zones, environmental devastation, changes in climate or legal structures (legislation on immigrant reception and residence, visa delivery…), not forgetting individual situations and aspirations, starting with those of women.

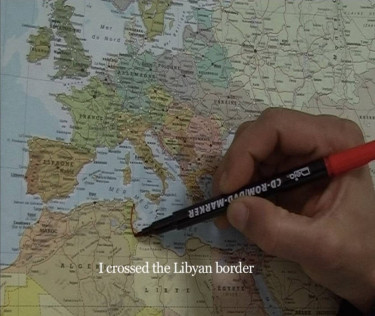

Legende

Bouchra Khalili, Mapping Journey #2. 2008 . Video, 3 mn. Musée national de l'histoire et des cultures de l'immigration © ADAGP, Paris 2011

Economic and demographic needs

Globally, populations and poverty can be found in the 175 developing countries, whereas 25 developed countries concentrate most of the world’s wealth – and its production. This situation, which should prompt a rethinking of the world economic order, represents and will continue to represent one of the driving forces behind future migration dynamics.

While in ageing European societies, immigration will only marginally contribute to maintaining the active population level, for certain populations and for a certain period, it will constitute the only demographic growth factor. To help curtail labour shortages, boost growth and competitiveness in whole sectors of the economy, the OECD will be calling on immigrants who are young, increasingly female, qualified – highly qualified even. This coincides with sociological evolutions in several departure countries, where candidates for emigration are mainly urban, educated, and among whom the proportion of women is growing. Nevertheless, less qualified immigrants are still needed, as was seen with the Covid health crisis and the labour shortages in the building trade, restaurant trade, and the industrial sector.

In contrast, professional prospects, the desire to escape socio-economic blockades or discrimination, and in recent years the effects of the crisis, are leading more and more young European and notably French graduates… to leave their country. So it’s no longer about immigrants here, and more about expatriates.

Diversification

While colonial history continues to leave its mark on the demographic structure of migrations to Europe, with globalisation, in other words greater mobility and increased exchanges, international migrations are tending to diversify, taking new paths, headed for new destinations. Hence Sri Lankans, Pakistanis and Chechens have arrived in France; Romanians, Poles, Albanians and Filipinos in Italy; Ukrainians in Spain and Portugal, Chinese in Africa... British people have left their country for the sunshine of France, Spain or Portugal, and while 83% of Algerian emigrants live in France, Algerians’ migration area is tending to expand to other European countries or towards the North-American continent. Migrations are globalising and while “only” 3.5% of the planet’s inhabitants have donned Rimbaud’s “soles of wind”, they are coming and they are travelling, on various scales, from everywhere.

Hence, new destinations have appeared: Gulf states, African continent, notably with Chinese migrations, Asian continent, and even former emigration countries turned host or transit countries: Portugal, Spain or even Mexico and Turkey, Morocco or Algeria. Five new countries known as the “BRICS” have emerged as attractive hubs: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa.

Migrations are globalising. They can also happen within the confines of national borders, for example the displacement of the “mingongs” or Chinese migrants in China, around 250 million of them, half of whom are undocumented in their own country. Determined by several factors (geographic, historic, cultural proximity, complementarities, existing migration networks…), migrations are also developing on a regional scale: Latin America and the Caribbean towards the USA, migration flows in South America; the Euro-Mediterranean area, Russia with Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan or the Chinese populations on the eastern border, etc.

Migrations and environment

Other population movements have appeared: "displaced people", "refugees" or climate and/or environmental "migrants". The plurality of terms expresses the legal vacuum around this new category of migrants. Likewise for debates on the size of forecasts and the diversity of situations: displacement inside the same country or straddling several countries; gradual or sudden deterioration of the environment; climate changes, flooding, tsunamis, desertification or deforestation, along with nuclear waste, collapsing dams or industrial disasters.

The Global Report on Internal Displacement 2020 by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre estimates that natural disasters caused the displacement of 25 million people in the year 2019 alone. “Since 2012, this is the highest figure ever recorded and three times more than displacements caused by conflicts and violence.”

In 2021, the World Bank estimated that by 2050 the number of people forced into climate-induced “displacement” could reach 216 million, i.e. 60 million more than forecasts for 2018 by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change).

According to the experts, these new forced migrations should take place on the scale of regions or of the countries concerned, in line with current internal migration trends and as a result of the poverty of the populations concerned.

For Kanta Kumari Rigaud, author of the World Bank report: “If countries start now to reduce greenhouse gases, close development gaps, restore vital ecosystems, and help people adapt”, these migrations could be reduced by 80%.

Mustapha Harzoune, 2022